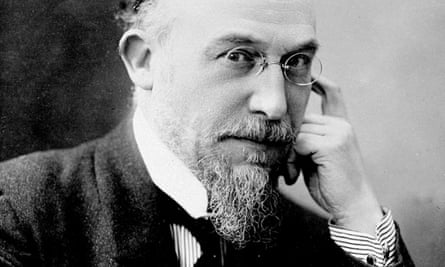

Film-makers have missed a trick with the life of Erik Satie. A biopic would have pretty much everything: the heart-warming story of a talented but strange man whose early failure and obscurity led to late-in-life celebrity; some acrobatic sex (literally – his one-and-only girlfriend had previously run away to the circus); strong language, violence, scandal and litigation (he was famously irascible, and was imprisoned over a spat with a music critic); the glamour of Paris, 1885-1925; more than walk-on roles for people like Stravinsky, Picasso and Diaghilev; the decadent Montmartre cabaret scene; oh, and a fabulous, ready-made score by the main man and his friends Debussy, Ravel and Poulenc.

With no such film yet in existence (Mike Leigh? Stephen Frears?), and with the 150th anniversary of Satie’s birth approaching, I thought I’d write in the meantime a musical theatre piece – a “theatrecital”? - for actor and pianist. Half monologue, half piano recital, its hour-plus span showcases the full, startling breadth of Satie’s piano output and interweaves an ageing Satie reflecting on his riotously varied, chaotically creative and intermittently dysfunctional life.

I’ve been fascinated by Satie’s life and music ever since writing sleeve notes for a recording of his piano music some 20 years ago. First, I was struck by the fact that his best known pieces, the Gymnopédies and Gnossiennes, are unrepresentative of a larger and later body of work that is much more quirky and revolutionary. And second, I was drawn to the eccentric sweep of his biography - much of which, as they say, you couldn’t make up.

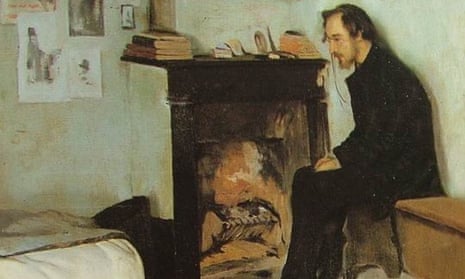

The stories of his peculiarity are legion. The one-man religious sect he established in Montmartre in the 1890s. The crazy titles of his piano pieces. The purchase of seven identical, grey velvet corduroy suits which he proceeded to wear, with no variation, for 10 years. His claim that he only ever ate food that was white. The omelette he is supposed to have eaten made from 30 eggs, or his consumption of 150 oysters in one go. And the most extraordinary, pathos-laden Satie-fact of all: that he moved from Montmartre in his late 20s to a tiny suburban bedsit and proceeded to live there until his death three decades later in 1925. No-one was ever allowed to visit in all those years, but for some stray dogs. When friends entered after his death, they witnessed indescribable squalor.

But it wasn’t all maverick eccentricity. It may be the timeless purity and melancholy of Satie’s Gymnopédie No 1 which has made it a pop classic, but it was Satie’s later output which is arguably more “important”, and which drew him to someone like John Cage, no less: “It’s not a question of Satie’s relevance. He’s indispensable,” was Cage’s famous tribute. Whether in the parodistic, collage-like piano miniatures written during world war one, or in his collaboration with Cocteau, Picasso and Diaghilev, Parade, there is a liveliness of imagination and bristling novelty which made Satie a torchbearer for the avant-garde in his later years. It is no coincidence that some of his closest friends, latterly, were radical artists such as Man Ray, Brancusi and Duchamp, or a much younger, go-ahead set of Paris-based composers such as Les Six.

Ravel and Debussy labelled Satie early on as a precursor, and not entirely as a compliment – Ravel qualified this with the adjectives “brilliant and clumsy”. But Satie’s visionary, pioneering later work took him way beyond his friends’ musical Impressionism. People such as Cage were excited by Satie’s desire to tear up the rule-book, to embrace the absurd and the surreal, to blend low and high art effortlessly. Satie was the first (known) composer to alter the sound of a piano by “preparing” it, back in 1914. Pieces like Vexations and Avant-dernières pensées are ‘minimalist’ many decades before Riley, Glass or Reich. Satie envisaged the first background music (what he called “furniture music”). And his music for René Clair’s 1925 surrealist film Entr’Acte was remarkable for being bespoke and synchronised with the pictures.

All pretty good firsts to notch up by the composer of that lovely, easy-on-the-ear Gymnopédie.

My piece of work – which has eventually acquired the title Erik Satie: Memoirs of a Pear-Shaped Life – is an act of assembly, the weaving of carefully-selected and -placed - music into a tapestry of text. Some of what Satie says is very much him, verbatim; he left a wealth of letters and other, sometimes impenetrably bizarre writings. Some of what we hear from him is taken from recollections and observations by close friends, such as his Montmartre chum and collaborator, writer JP Contamine de Latour. Lines of his such as “We didn’t eat every day, but we never missed an aperitif” were too good to pass up.

And then there is a reasonable amount of text by me – perhaps more than I expected when I started out, because, perhaps optimistically, I thought that with all the rich Satie-and-friends source material, it would merely be a cut-and-paste job. It soon became apparent that more subtlety was required; my role as assembler-writer has been to shape the narrative and music around each other, and to attempt to present a complex psychological profile that encompasses his loneliness, his likeableness, his violent temper, his brilliance, his early shutdown to intimacy – and his downright strangeness.

- Eric Satie: Memoirs of a Pear-Shaped Life is at the Parabola Arts Centre, Cheltenham with Anne Lovett and David Bamber in on Thursday 2 July. Meurig Bowen is Director of the Cheltenham Music Festival, which runs from 30 June-11 July. Various venues. www.cheltenhamfestivals.com/music

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion